How to build your Customer Success calendar as a CSM

As a CSM, I tried really hard to think ahead and put stuff on my Customer Success calendar. Even with meticulous planning, projects seemed to take about 5X longer than anticipated, and deadlines flew by like Tom Cruise in an F-14 (an excellent Top Gun reference).

My brain seemed to work against me when estimating how much time something should take. Back when I led the CS team at a startup in an exponential growth phase, this bit me in the ass all the time. Here’s an example of a situation I found myself in all too often:

- Get an email from a customer asking for custom work on their implementation.

- Feel obligated to say “yes”, since we’re on the rocks with this account.

- Say something dumb, like “if I really hustle, I can get this done in 90 minutes!”

- Things get complicated 20 minutes in, and 90 minutes turns into three hours.

- Realize I ignored three hours of pre-scheduled work to get this done.

- Shut laptop, go to happy hour for a break.

- Suppress urge to hysterically laugh-cry when bartender asks how I’m doing.

- Stay at the office way too late again to make up for lost time.

Unfortunately, this situation was part of a bigger cycle I wasn’t aware of at the time. One of the most effective ways to perpetuate this cycle was to fall into the blame-trap. Here’s the same scenario from before, except through a highly-polished blame lens:

- The product team should have spent more time thinking this feature through – it’s totally overwhelming to document. I’ll check my email instead.

- I have to say “yes” to this request for custom work because sales over-sold the product, and now I have to clean up the mess to save the customer.

- Our project-management tool sucks, so I’ll just guesstimate the time it will take.

- The technology stack we use is ancient and stupid, making this simple task take forever.

- If yesterday hadn’t been so crazy, maybe I’d eat healthier today.

- Maybe if we had more CSMs, I wouldn’t have to stay late at the office every night this week.

In retrospect, it’s easy to see where I went wrong. Here’s a breakdown of the situation I outlined above, except through a more objective lens:

- I checked email during a time slot I designated to write documentation (hint: this is where things went wrong).

- I got sidetracked by a customer asking for custom work.

- I immediately felt guilty our documentation wasn’t better, and said “yes” to try and make up for it.

- Instead of taking the time to scope out the project, I made an arbitrary estimate I thought would sound good to the customer.

- I immediately felt overwhelmed because I over-promised, knowing I’d most likely under-deliver.

- Beer/distraction time!

- I deferred all the tasks I scheduled for the afternoon to the next day so I could finish the thing I promised the customer.

The three scenarios above are exactly the same, I just framed them differently. I presented the first as “a bunch of things that happened to me”, the 2nd as “all the reasons they happened to me”, and the 3rd as “a bunch of things I did to make this happen”.

This distinction yields an undeniable conclusion:

We cannot begin to see things for what they were until we’re willing to be honest with ourselves about the role we played in them.

If any of this sounds like something you’ve experienced in the past week, you’re totally not alone. There’s a way through this! First, I have a question for you:

Are you ready to be brutally honest about how you spent your time yesterday afternoon?

If you’re not quite ready to get specific, that’s ok – but the rest of this post might not be useful for you. Feel free to watch this cat gif instead!

Still with us? Sweet – let’s get to work.

The premise of this exercise is simple: awareness is the first step to understanding something. Whether or not we’re aware of how we spent our time, it done got spent, so let’s figure out what we did yesterday afternoon.

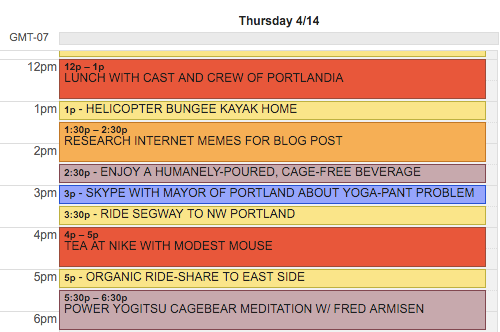

Step 1: Take a snapshot of what your schedule was supposed to look like from noon to 6:00pm yesterday.

Here’s my example:

I love to plan my ideal life into neat little 30-60 minute increments; makes me feel like I’m doing it right. In this example however, I’m an amateur CSM. Therefore, my schedule rarely falls in line with what’s ideal.

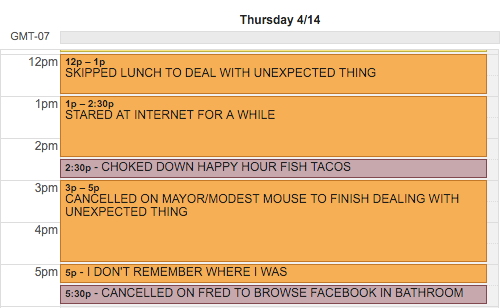

Step 2: Take a snapshot of what your schedule actually looked like from noon to 6:00pm yesterday.

I’ll take the lead on this again:

Holy discrepancy, Batman! What happened?! That’s not the legendary day I meticulously planned 🙁

Step 3: Figure out what you could have said “no” to.

In my larger-than-life example, I got an email from an angry customer at 11:29am yesterday. This was moments before I was supposed to rollerblade to meet Carrie and Fred for lunch in the Pearl district. Since I’m a CSM, my inclination is to put the needs of others above my need for dim sum with celebrities. As a result, I skipped lunch to help the customer.

If you’re saying to yourself “well, you should have said NO to the customer and taken lunch, you dummy!”, you might be right. However, I believe this thing goes #deeper.

What happened before I decided to cancel lunch plans?

I checked my email.

Why did I check my email at 11:29am? If I were an Elite CSM, I’d have time slots booked on my calendar designated for processing inboxes. However, like a lot of people with smartish phones, I’m in the mindless habit of checking my email all the time, simply because I can.

That’s where things went wrong. When I felt the nervous impulse to check email, I could have said “NO! My calendar doesn’t say ‘check email’, it says ‘rollerblade to dumpling town’, so I’ma do THAT.”

Unfortunately, the decision to randomly check email derailed my entire day and made me sad. Even worse, there were some hidden, but profound consequences. We’ll get to those in step 4, but first we need to accept one more premise. Ready?

A calendar is a machine designed to help us do what we said we were going to do.

Think about the implications of such a redefinition. Did that just blow your mind?

Step 4: Write down what might happen if you fail to do what you said you were going to do.

For this part of the exercise, we’re going to utilize our loss-aversion psychology and focus on the worst-case scenario.

Here’s what mine looks like:

- I failed to live up to a commitment I made to myself to only check inboxes during pre-determined times, and now I question my ability to stick to my own commitments.

- I let myself get sidetracked by a customer, which ruined my afternoon. Now I’m questioning my ability to enforce my own boundaries.

- I acted on feelings of guilt, instead of empowerment, which is something I promised myself I’d never do again.

- I told a customer what they wanted to hear instead of what was true, thus diluting the credibility of myself, my managers, and my product.

- I didn’t want to seem like an idiot, so instead of immediately addressing the customer and renegotiating expectations, I cancelled all my previous commitments and pressed on.

- I deferred all the tasks I scheduled for the afternoon to the next day so I could finish the thing I promised the customer.

With such an exercise, the reality of a situation emerges quickly, doesn’t it? In retrospect, the reason we most likely end up in these kinds of situation is out of fear.

In this example, the thing I’m most afraid of is losing my credibility. Ironically, the path I took to salvage my credibility damaged it far more than it helped.

Instead of making this a personal problem or an issue of “self”, let’s reframe this as a process problem. How can we improve the process so it doesn’t fail?

Let’s do some abstraction. Here’s a crude equation I can derive from this scenario:

LETTING MYSELF GET DERAILED = CANCELLING PLANS = LOSS OF CREDIBILITY

Another way to write this equation is:

STAY ON TRACK = KEEP CREDIBILITY

The 2nd version of this equation reveals the solution. My calendar is a machine designed to help me stay on track, so all I have to do is trust it.

Getting to a point where you implicitly trust your calendar takes practice, preparation, self-awareness, and a bit of discipline. Without an underlying drive to do keep commitments to yourself, you may always fall short of consistently following through on commitments to others.

Want more Customer Success Manager insights? Keep reading…

- How to stop firefighting and start managing your time as a CSM

- The strategic conversation playbook for Customer Success Managers

- Documentation: the silver bullet for your Customer Success team